Having such an abundance of historical resources at our fingertips in recent years can be intimidating to both new and experienced teachers in the field. While upon first glance this may seem like an obstacle to our teaching of history, it’s really an opportunity to teach our students some of the fundamentals of doing history. This semester, I’ve learned that it’s important to embrace the challenge of the abundance of historical information to which we have access, to think outside the box when it comes to creating assignments that give students applicable historical skills, and to consider implementing new digital tools into our lessons to provide our students with the most enriching experience with history that we can.

Abundance

The abundance of historical knowledge available to us and our students is only valuable to us and our students if we know how to use it. In Madsen-Brooks’ “’I Nevertheless Am a Historian’” piece, it is well stated: the abundance of digital tools and historical resources accessible to us today are “…not only democratizing historical practice but also providing professional historians with new opportunities and modes for expanding historical literacy” (Madsen-Brooks, 50). As a history teacher, I feel it’s a duty of mine to teach my students how to appropriately apply digital tools to enhance their research. After all, having a wealth of primary sources is only valuable if you know what to do with them! Even these digital tools that allow us to more easily access and store historical information need to be taught in order to be democratized. Even if my students never go on to be historians by profession, they will go on with the skills they need to make historical analyses and discoveries on their own.

So, how do we teach our students how to utilize the tools available to them in the world of digital history?

One of the most obvious, yet most taboo learning tools we have is in the back pocket of almost every student in our classrooms. Teaching our students the proper way to utilize their cell phones is a skill that extends beyond the classroom, and is a valuable lesson for our students, whether or not it’s a part of the curriculum (Sterner). Instead of outright banning such a powerful tool, we should be teaching our students what we know about using it for good! Teachers and historians alike use their phones daily, often in ways that benefit their academic and historical endeavors. Teaching our students the simple knowledge of proper use of this device for the historical tasks at hand can, as Madsen-Brooks discusses, democratize historical practice and give everyone the ability to be a stronger historian. Additionally, the distraction that the phone causes will not go away if we pretend it’s not there. Our students will use their cell phones outside of the classroom no matter what, and part of setting them up for success is teaching them the ways to do and analyze history in that digital space.

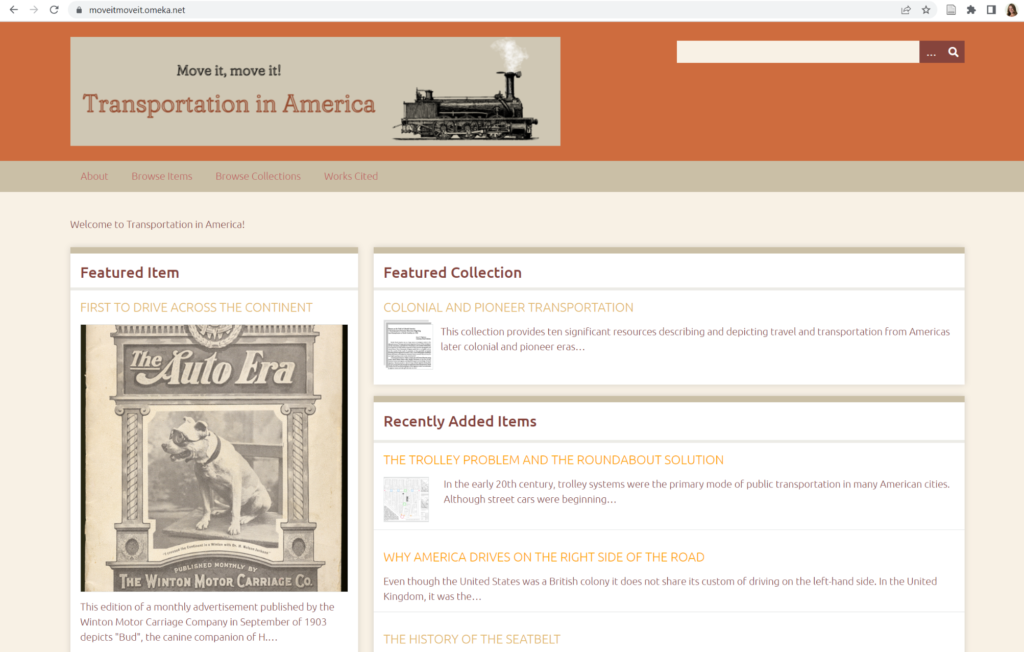

Another way we can enrich our students’ historical experience is by getting creative with our assignments. The first time I had such an explicit opportunity in a classroom to work outside the box with historical exploration was on our Omeka project, where I learned lessons on both of the concepts I discussed above. The Omeka project allowed me to utilize types of technology that I never had before in the history classroom, and also challenged me to think critically about the abundance concept – it was more challenging than I thought it would be to narrow my pool of sources down to what I perceived to be the most important ones! This is a project that I see myself emulating in some way in my future classroom. Not only did it allow students to go about discovering a historical topic in their own way, it allowed them to explore why historians choose to present the evidence they do in making a historical argument. As Megan Brett discusses in “’Can’t We Just Write a Paper?’”, students will be challenged by doing this sort of digital archiving, but will more often than not appreciate the skills they gained from such a challenge, and walk away with more knowledge of how and why we do history the way we do than they would have if assigned a more rigid, essay-like assignment on the same topic.

How I’ll teach with what I learned in Teaching History with New Media

My biggest takeaway from HIS 3630 was how important it is to teach students the relevance of history in the digital space. If they understand how and why we archive and explore history the way we do in the digital age, they are more likely to come out of our classrooms as better critical thinkers who aren’t intimidated by a field of study that can often seem overwhelming to those who don’t do it professionally. My goal as a history teacher is to equip my students with the tools (physical, digital, and intellectual) to evaluate and do history in their everyday lives.

Works Cited

Brett, Megan. “‘Can’t We Just Write a Paper?’ Digital Galleries and Archival Research for Undergraduates.” Omeka.org, August 16, 2016, https://omeka.org/news/2016/08/16/gp-cant-we-just-write-a-paper/.

Madsen-Brooks, Leslie. “‘I Nevertheless Am a Historian: Digital Historical Practice and Malpractice around Black Confederate Soldiers.” In Writing History in the Digital Age, edited by Jack Dougherty and Kristen Nawrotzki, 49-63. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv65sx57.

Sterner, Rob. “4 Things You’ll Miss by Banning Cellphones In Your Classroom,” Teaching Quality. Last modified February 24, 2015. https://www.teachingquality.org/4-things-youll-miss-by-banning-cellphones-in-your-classroom/.